Assessments

Scope of this chapter

After a Children’s Social Care Department accepts a referral a social worker qualified practice supervisor or manager should initiate a multiagency assessment under section 17 of the Children Act 1989.

Assessments must be based on good analysis, timeliness and transparency and be proportionate to the needs of the child and their family. The assessment must be approved by a social work qualified Practice Supervisor or manager. Different levels of assessment determine which services are commissioned and delivered to ensure that the right help is given to children at the right time.

Each child who has been referred to local authority children's social care should have an individual assessment to identify their needs and to understand the impact of any parental behaviour on them as an individual. Local authorities have to give due regard to a child's age and understanding when determining what (if any) services to provide under Section 17 of the Children Act 1989, and before making decisions about action to be taken to protect individual children under Section 47 of the Children Act 1989.

This should also include a range of appropriate services for disabled children.

Related guidance

- Working Together to Safeguard Children - Assessment

- Social work post-qualifying standards: knowledge and skills statements

Amendment

This chapter was refreshed in December 2024.

Under the Children Act 1989, local authorities undertake assessments of the needs of individual children to determine what services to provide and what action to take:

- A child in need is defined under the Children Act 1989 as a child who is unlikely to achieve or maintain a satisfactory level of health or development, or their health and development will be significantly impaired, without the provision of services; or a child who is disabled. In these cases, Assessments by a social worker are carried out under Section 17 of the Children Act 1989. Children in Need may be assessed under section 17 of the Children Act 1989, in relation to their Special Educational Needs, disabilities, or as a carer, or because they have committed a crime. The process for assessment should also be used for children whose parents are in prison and for unaccompanied migrant children and child victims of modern slavery. When assessing Children in Need and providing services, specialist assessments may be required and, where possible, should be coordinated so that the child and family experience a coherent process and a single plan of action.

The need to assess can also include pre-birth situations when a mother's own circumstances would give cause for concern that the unborn/ born child would come within the definition of being a 'Child in Need' (see Section 11.1, Pre-birth 'Good Practice Steps'); - Concerns about maltreatment may be the reason for a referral to local authority children's social care or concerns may arise during the course of providing services to the child and family. In these circumstances, local authority children's social care must initiate enquiries to find out what is happening to the child and whether protective action is required. Local authorities, with the help of other organisations as appropriate, also have a duty to make enquiries under Section 47 of the Children Act 1989 if they have reasonable cause to suspect that a child is suffering, or is likely to suffer, significant harm, to enable them to decide whether they should take any action to safeguard and promote the child's welfare. Such enquiries, supported by other organisations and agencies as appropriate, should be initiated where there are concerns about all forms of abuse and neglect. This includes female genital mutilation and other honour-based violence, and extra-familial threats including radicalisation and sexual or criminal exploitation;

- There may be a need for immediate protection whilst the assessment is carried out;

- Some Children in Need may require accommodation because there is no one who has parental responsibility for them, or because they are alone or abandoned. Under Section 20 of the Children Act 1989, the local authority has a duty to accommodate such Children in Need in their area. Following an application under Section 31A, where a child is the subject of a care order, the local authority, as a corporate parent, must assess the child's needs and draw up a care plan which sets out the services which will be provided to meet the child's identified needs.

Whatever legislation the child is assessed under, the purpose of the assessment is always:

- To gather important information about a child and family;

- To analyse their needs and/or the nature and level of any risk and harm being suffered by the child, including where the harm or risk of harm is from outside the home;

- To decide whether the child is a Child in Need (Section 17) and/or is suffering or likely to suffer Significant Harm (Section 47);

- Identify support from within the family network;

- To provide support to address those needs to improve the child's outcomes and welfare and, where necessary, to make them safe;

- To identify support from within the family network.

Assessments for some children will require particular care. This is especially so for:

- Young carers;

- Children with special educational needs - including being informed by, and informing, Education, Health and Care Plans. See also Children and Young People Aged 0-25 With Special Educational Needs and Disabilities Procedure;

- Unborn children where there are concerns regarding the parent(s);

- Children in hospital;

- Children with specific communication needs;

- Unaccompanied migrant children - see also Unaccompanied Asylum Seeking Children Procedure;

- Children considered at risk of gang activity and association with organised crime groups;

- Children at risk of female genital mutilation;

- Children who are in the youth justice system - see also Child in Care and Children in Contact with Youth Justice Services Procedure; and

- Children returning home following a period of Accommodation.

Every assessment must be informed by the views of the child as well as the family, and a child's wishes and feelings must be sought regarding the provision of services to be delivered.

The assessment will involve drawing together and analysing available information from a range of sources, including existing records, and involving and obtaining relevant information from professionals in relevant agencies and others in contact with the child and family. Where an Early Help Assessment has already been completed this information should be used to inform the assessment. The child and family's history should be understood.

Where a child is involved in other assessment processes, these must be coordinated so that the child does not become lost between the different agencies involved and their different procedures. All plans for the child developed by the various agencies and individual professionals should be joined up so that the child and family experience a single assessment and planning process, which shares a focus on the outcomes for the child.

The social worker should analyse all the information gathered from the enquiry stage of the assessment to decide the nature and level of the child's needs and the level of risk, if any, they may be facing. Practitioners should have access to high-quality supervision from a Practice Supervisor who will help challenge their assumptions as part of this process.

Practitioners play a crucial role in assessing and planning care for individuals. While it is important to maintain a positive outlook and hope for adults to overcome their challenges, this should not compromise the safety and wellbeing of children. Practitioners should stay informed by the latest research on the impact of abuse, neglect, and exploitation. Additionally, insights from serious case and practice reviews should guide their assessment of the child’s level of need and risk.

All of this information should be reflected in the case records.

Critical reflection through supervision should strengthen the analysis in each assessment. An informed decision should be taken on the nature of any action required and which services should be provided. Social workers, their managers and other professionals should be mindful of the requirement to understand the level of need and risk in a family from the child's perspective and ensure action or commission services which will have the maximum positive impact on the child's life. Where there is a conflict of interest, decisions should be made in the child's best interests, be rooted in child development, be age-appropriate, and be informed by evidence.

When new information comes to light or circumstances change the child's needs, any previous conclusions should be updated and critically reviewed to ensure that the child is not overlooked as noted in many lessons from serious case and practice reviews.

An assessment for Early Help can be undertaken by a Lead Practitioner who is not necessarily a qualified social worker.

Assessments for Early Help should consider how the needs of different family members impact on each other. This includes needs relating to education, mental and physical health, financial stability housing, substance use and crime. Specific needs should be considered such as disabilities, those whose 1st language isn’t English, fathers or male carers, and parents who identify as LGBTQ+. Early Help services may focus on improving family functioning and developing the family’s capacity to establish positive routines and solve problems. Where family networks support the child and parents, services may take an approach that enables family group decision-making, such as a family group conference.

The safeguarding partnership publishes a Threshold Document which sets out the criteria for early help.

In the case of child protection enquiries (section 47 Children Act 1989), the assessment should be led by a qualified and experienced social worker with the appropriate skills, knowledge and capacity to carry out the assessment. The practitioner must be regularly supervised by a social work manager. Principal social workers should support Practitioners, the local authority and partners to develop their assessment practice and decision-making skills, and the practice methodology that underpins this.

The date of the commencement of the assessment will be recorded in the electronic database.

The qualified social worker should carefully plan that the following are carried out:

- See/interview the child;

- Interview the parents and any other relevant family members;

- Consider whether to see the child with their parents;

- The child should be seen by the lead social worker without their caregivers when appropriate and this should be recorded in the Assessment Record;

- Determine what the parents should be told of any concerns;

- Consult with, and consider contributions from, all relevant agencies, including agencies covering previous addresses in the UK and abroad.

If it is determined that a child should not be seen as part of the assessment, this should be recorded by the manager with an explanation for this decision.

Before a Referral is discussed with other agencies, the parent's consent should usually be sought, unless doing so may place the child at risk of Significant Harm, in which case the manager should authorise the discussion of the Referral with other agencies without parental knowledge or consent. The authorisation should be recorded with reasons.

If during, the course of the assessment, it is discovered that a school-age child is not attending an educational establishment, the social worker should contact the local education service to establish a reason for this.

If there is suspicion that a crime may have been committed including sexual or physical assault or neglect of the child, the Police must be notified immediately.

In planning the assessment and in providing the parent and child with feedback, the person undertaking the assessment will need to consider and address any communication issues, for example, language or impairment.

Where a child or parent speaks a language other than that spoken by the practitioner, such as those who are unaccompanied children and those children who are victims of modern slavery and/or trafficking, an interpreter should be provided. Any decision not to use an interpreter in such circumstances must be approved by the Team Manager and recorded.

Where a child or parent with disabilities has communication difficulties it may be necessary to use alternatives to speech. In communicating with a child with such an impairment, it may be particularly useful to involve a person who knows the child well and is familiar with the child's communication methods. However, caution should be exercised in using family members to facilitate communication. Where the child has had a communication assessment, its conclusions and recommendations should be observed.

NOTE: Where the parents have learning disabilities, it may be necessary to adapt communications to meet their needs – for further information, see West Berkshire LSCP Procedures, Children of Parents with Learning Disabilities Procedure and the Good Practice Guidance on Working with Parents with a Learning Disability (Working Together with Parents Network).

Children should be seen and listened to and included throughout the assessment process. Their ways of communicating should be understood in the context of their family and community as well as their behaviour and developmental stage. It is important that the impact of what is happening to a child is clearly identified and that information is gathered, recorded and checked systematically, and discussed with the child and their parents/carers where appropriate.

Assessments should review the impact of the assessment process and the services provided to the child so that the best outcomes for the child can be achieved. Any services provided should be based on a clear analysis of the child's needs, and the changes that are required to improve the outcomes for the child.

Children should be actively involved in all parts of the process based on their age, developmental stage and identity. Direct work with the child and family should usually include observations of the interactions between the child and the parents/caregivers.

All agencies involved with the child, the parents and the wider family have a duty to collaborate and share information to safeguard and promote the welfare of the child.

All assessments should be planned and coordinated by a social worker and the purpose of the assessment should be transparent, understood and agreed by all participants. There should be an agreed statement setting out the aims of the assessment process.

The timing of an assessment following a child’s case referral to Children’s Social Care should align with the child’s specific needs and the level of risk they face. Qualified Practice Supervisors or managers must make individual judgments for each case. Similarly, assessments of adult parent/carers or non-parent carers, should also be conducted promptly.

Referrals may include siblings or a single child within a sibling group. Where the initial focus for a referral is on one child, other children in the household or family should be equally considered, and the individual circumstances of each assessed and evaluated separately.

Planning should identify the different elements of the assessment including who should be involved. It is good practice to hold a planning meeting to clarify roles and timescales as well as services to be provided during the assessment where there are a number of family members and agencies likely to play a part in the process.

Questions to be considered in planning assessments include:

- Who will undertake the assessment and what resources will be needed?

- Who in the family will be included and how will they be involved (including absent or wider family and others significant to the child)?

- In what grouping will the child and family members be seen and in what order and where?

- What services are to be provided during the assessment?

- Are there communication needs? If so, what are the specific needs and how they will be met?

- How will the assessment take into account the particular issues faced by black and minority ethnic children and their families, and disabled children and their families?

- What method of collecting information will be used? Are there any tools/questionnaires available?

- What information is already available?

- What other sources of knowledge about the child and family are available and how will other agencies and professionals who know the family be informed and involved?

- How will the consent of family members be obtained?

- What will be the timescales?

- How will the information be recorded?

- How will it be analysed and who will be involved?

- When will the outcomes be discussed and service planning take place?

The assessment process can be summarised as follows:

- Gathering relevant information;

- Analysing the information and reaching professional judgments;

- Making decisions and planning interventions;

- Intervening, service delivery and/or further assessment;

- Evaluating and reviewing progress.

Assessment should be a dynamic process, which analyses and responds to the changing nature and level of need and/or risk faced by the child from within and outside their family. A good assessment will monitor and record the impact of any services delivered to the child and family and review the help being delivered. Whilst services may be delivered to a parent or carer, the assessment should be focused on the needs of the child and on the impact any services are having on the child.

Child-centred assessments should clearly articulate the child’s perspective and reflect the lived experience of the child. Decisions should be made with the child’s best interests in mind, considering their developmental stage, age-appropriateness, and sensitivity to adversity and trauma.

Observations play a crucial role, especially for babies, infants, and non-verbal children. When assessing disabled children, practitioners should assess the need for specialised communication support and explore how advocacy services can facilitate the child’s communication of their views.

See: Berkshire West Safeguarding Children Partnership, Listening to the Voice of the Child Procedure.

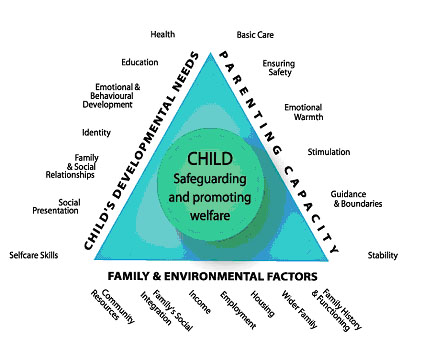

Research has demonstrated that taking a systematic approach to assessments using a conceptual model is the best way to deliver a comprehensive analysis. A good assessment is one which investigates the three domains set out in the Assessment Framework Triangle.

Children may be vulnerable to neglect and abuse or exploitation from within their family but increasingly also from individuals they come across in their day-to-day lives. These threats can take a variety of different forms, including sexual, physical and emotional abuse; neglect; exploitation by criminal gangs and organised crime groups; trafficking; online abuse; sexual exploitation and the influences of extremism leading to radicalisation.

The interaction of these domains requires careful investigation during the Assessment. The aim is to reach a judgement about the nature and level of needs and/or risks that the child may be facing within their family and/or community. Importantly the assessment, in looking at the domains, should also consider where the strengths are in a child's circumstances and in what way they may assist in reducing the risk.

An assessment should establish:

- The nature of the concern and the impact this has had on the child;

- An analysis of their needs and/or the nature and level of any risk and harm being suffered by the child;

- How and why the concerns have arisen;

- What the child's and the family's needs appear to be and whether the child is a Child in Need;

- Whether the concern involves neglect, and the influence on this of the wider family and other adults living in the household, as well as community and environmental circumstances;

- Whether there is any need for any urgent action to protect the child, or any other children in the household or wider community;

- Whether any factors may indicate that the child is being or has been criminally or sexually exploited or trafficked;

- Note: if there is a concern with regard to trafficking, a referral to the National Referral Mechanism should be made. See GOV.UK, Digital Referral System: Report Modern Slavery.

The child should participate and contribute directly to the assessment process based on their age, understanding and identity. They should be seen alone and if this is not possible or in their best interests, the reason should be recorded. The social worker should work directly with the child to understand their views and wishes, including how they behave both with their caregivers and in other settings. The agreed local assessment framework should make a range of age-appropriate tools available to professionals to assist them in this work.

The pace of the assessment needs to acknowledge the pace at which the child can contribute. However, this should not be a reason for delay in taking protective action. It is important to understand the resilience of the individual child in their family and community context when planning appropriate services.

Every assessment should be child-centred. Where there is a conflict between the needs of the child and their parents/carers, decisions should be made in the child's best interests. The parents should be involved at the earliest opportunity unless doing so would prejudice the safety of the child.

The parents’ involvement in the assessment will be central to its success. At the outset, they need to understand how they can contribute to the process and what needs to change in order to improve the outcomes for the child. The assessment process must be open and transparent with the parents. However, the process should also challenge parents' statements and behaviour where it is evidenced that there are inconsistencies, questions or obstacles to progress. All parents or caregivers should be involved equally in the assessment and should be supported to participate whilst the welfare of the child must not be overshadowed by parental needs. There may be exceptions to the involvement, in cases of Sexual Abuse or Domestic Violence and Abuse for example, where the plan for the assessment must consider the safety of an adult as well as that of the child.

The child should participate and contribute directly to the assessment process based upon their age, understanding and identity. They should be seen alone and if this is not possible or in their best interests, the reason should be recorded. The social worker should work directly with the child in order to understand their views and wishes, including the way in which they behave both with their caregivers and in other settings. The agreed local assessment framework should make a range of age appropriate tools available to professionals to assist them in this work.

The pace of the assessment needs to acknowledge the pace at which the child can contribute. However, this should not be a reason for delay in taking protective action. It is important to understand the resilience of the individual child in their family and community context when planning appropriate services.

Every assessment should be child-centred. Where there is a conflict between the needs of the child and their parents/carers, decisions should be made in the child's best interests. The parents should be involved at the earliest opportunity unless to do so would prejudice the safety of the child.

The parents' involvement in the assessment will be central to its success. At the outset they need to understand how they can contribute to the process and what needs to change in order to improve the outcomes for the child. The assessment process must be open and transparent with the parents. However, the process should also challenge parents' statements and behaviour where it is evidenced that there are inconsistencies, questions or obstacles to progress. All parents or caregivers should be involved equally in the assessment and should be supported to participate whilst the welfare of the child must not be overshadowed by parental needs. There may be exceptions to the involvement, in cases of Sexual Abuse or Domestic Violence and Abuse for example, where the plan for the assessment must consider the safety of an adult as well as that of the child.

All agencies and professionals involved with the child, and the family, have a responsibility to contribute to the assessment process. This might take the form of providing information promptly and direct or joint work. Differences of opinion between professionals should be resolved speedily but, where this is not possible, the local arrangements for resolving professional disagreements should be implemented (see West Berkshire Local Safeguarding Children Partnership Procedures Manual, Resolving Professional Difference of Opinion and Escalation).

It is possible that professionals have different experiences of the child and family and understanding these differences will actively contribute to the understanding of the child / family.

The professionals should be involved from the outset and through the agreed, regular process of review.

The social worker's supervisor will have a key role in supporting the practitioner to ensure that all relevant agencies are involved.

Agencies providing services to adults, who are parents, carers or who have regular contact with children, must consider the impact on the child of the particular needs of the adult in question.

Every assessment should be focused on outcomes, deciding which services and support to provide to deliver improved welfare for the child and reflect the child's best interests. In the course of the assessment, the social worker and their line manager should determine:

- Is this a Child in Need? (section 17 Children Act 1989);

- Is there reasonable cause to suspect that this child is suffering, or is likely to suffer, significant harm? (section 47 Children Act 1989);

- Is this a child in need of accommodation? (Section 20 or Section 31A Children Act 1989).

The possible outcomes of the assessment should be decided on by the social worker and their line manager, who should agree a plan of action setting out the services to be delivered, how and by whom, in discussion with the child and family and the professionals involved.

The outcomes may be as follows:

- No further action;

- Additional support which can be provided through universal services and single service provision or the early help process;

- The development of a multi-agency Child in Need plan for the provision of child in need services to promote the child's health and development;

- Specialist assessment for a more in-depth understanding of the child's needs and circumstances;

- Undertaking a strategy discussion/meeting/a Section 47 child protection enquiry;

- Emergency action to protect a child.

The outcome of the assessment should be:

- Discussed with the child and family and provided to them in written form. Exceptions to this are where this might place a child at risk of harm or jeopardise an enquiry or a police investigation;

- Taking account of confidentiality, provided to professional referrers;

- Given in writing to agencies involved in providing services to the child with the action points, review dates and intended outcomes for the child stated.

The maximum time frame for the assessment to conclude, such that it is possible to reach a decision on the next steps, should be no longer than 45 working days from the point of referral. If, in discussion with a child and their family and other professionals, an assessment exceeds 45 working days, the social worker and professionals involved should record the reasons for exceeding the time limit. In some cases, the needs of the child will mean that a quick assessment will be required. In all cases, as practitioners identify needs during the assessment, they do not need to wait until the assessment concludes before providing support or commissioning services to support the child and their family.

In a High Court judgment (Nottingham City Council v LW & Ors [2016] EWHC 11(Fam) (19 February 2016)) Keehan J set out five points of basic and fundamental good practice with respect to public law proceedings regarding pre-birth and newly born children and particularly where children's social care services are aware at a relatively early stage of the pregnancy.

In respect of assessment, these good practice steps were:

- A risk assessment of the parent(s) should 'commence immediately upon the social workers being made aware of the mother's pregnancy';

- Any assessment should be completed at least 4 weeks before the mother's expected delivery date;

- The Assessment should be updated to take into account relevant events pre - and post delivery where these events could affect an initial conclusion in respect of risk and care planning of the child;

- The assessment should be disclosed upon initial completion to the parents and, if instructed, to their solicitor to give them the opportunity to challenge the Care Plan and risk assessment.

The assessment plan must set out timescales for the actions to be met and stages of the assessment to progress, which should include regular points to review the assessment. The work with the child and family should ensure that the agreed points are achieved through regular reviews. Where delays or obstacles occur these must be acted on and the assessment plan must be reviewed if any circumstances change for the child.

The social worker's line manager must review the assessment plan regularly with the social worker and ensure that actions such as those below have been met:

- There has been direct communication with the child alone and their views and wishes have been recorded and taken into account when providing services;

- All the children in the household have been seen and their needs considered;

- The child's home address has been visited and the child's bedroom has been seen;

- The parents have been seen and their views and wishes have been recorded and taken into account;

- The analysis and evaluation has been completed;

- The assessment provides clear evidence for decisions on what types of services are needed to provide good outcomes for the child and family.

'Working Together to Safeguard Children' reminds all professionals of the importance of reviewing progress and that a high quality assessment is one in which evidence is built and revised throughout the process and takes account of family history and the child's experience of cumulative abuse. A social worker may arrive at a judgement early in the case but this may need to be revised as the case progresses and further information comes to light. It is a characteristic of skilled practice that social workers revisit their assumptions in the light of new evidence and take action to revise their decisions in the best interests of the individual child. Decision points and review points involving the child and family and relevant practitioners should be used to keep the assessment on track. This is to ensure that help is given in a timely and appropriate way and that the impact of this help is analysed and evaluated in terms of the improved outcomes and welfare of the child.

Recording by all professionals should include information on the child's development so that progress can be monitored to ensure their outcomes are improving. This is particularly significant in circumstances where neglect is an issue.

Records should be kept of the progress of the assessment on the individual child's record and in their chronology to monitor any patterns of concerns.

Assessment plans and action points arising from plans and meetings should be circulated to the participants including the child, if appropriate, and the parents.

The recording should be such that a child, requesting to access their records, could easily understand the process taking place and the reasons for decisions and actions taken.

Supervision records should reflect the reasoning for decisions and actions taken.

Where a 16 or 17 year old seeks help from local authority children's services, or is referred to children's services by some other person or agency as appearing to be homeless or threatened with homelessness, children's services must carry out an assessment of what duties, if any, are owed to them. This includes 17 year olds who are approaching their 18th birthday, and young people who are pregnant or have children in their care.

If there is an imminent threat of homelessness, or if the young person is actually homeless, a child in need assessment must be carried out and the child accommodated under section 20 Children Act 1989, (although this can be refused by the child) (see Prevention of Homelessness and Provision of Accommodation for 16 and 17 year olds who may be Homeless and/or require Accommodation; and Duty to Refer).

Intentional Homelessness see: Homelessness Guidance for local authorities.

An increasing number of cases involve families from abroad, necessitating assessments of family members in other countries. However, the Court of Appeal has pointed out that it might not be professional, permissible or lawful for a social worker to undertake an assessment in another jurisdiction. Children and Families Across Borders (CFAB) advise that enquiries should be made as to whether the assessment can be undertaken by the authorities in the overseas jurisdiction. UK social workers should not routinely travel overseas to undertake assessments in countries where they have no knowledge of legislative frameworks, cultural expectations or resources available to a child placed there.

See also: Cross-border child protection cases: the 1996 Hague Convention (DfE) and The International Child Abduction and Contact Unit.

As well as threats to the welfare of children from within their families, children may be vulnerable to abuse or exploitation from outside their families. This is often referred to as extra-familial harm. These extra-familial threats might arise at school and other educational establishments, from within peer groups, or more widely from within the wider community and/or online.

Children may experience this type of harm from other children and/or from adults. Forms of extra-familial harm include exploitation by criminal and organised crime groups and individuals (such as county lines and financial exploitation), serious violence, modern slavery and trafficking, online harm, sexual exploitation, teenage relationship abuse, and the influences of extremism which could lead to radicalisation. Children of all ages can experience extra-familial harm.

Where children may be experiencing extra-familial harm, children’s social care assessments should determine whether a child is in need under section 17 or section 47 of the Children Act 1989.

Assessments of children in such cases should consider whether wider environmental factors are undermining effective intervention being undertaken to reduce risk with the child and family. Parents and carers have little influence over the contexts in which the abuse takes place and the young person's experiences of this extra-familial abuse can undermine parent-child relationships.

A good assessment should:

- Build an understanding of the child’s strengths, interests, identity, and culture;

- Respond to each of the vulnerabilities and/or challenges that the child may be facing, including any within the home;

- Gather information on past experiences of trauma and how this may impact on the child’s current experience of harm and on how they interact with practitioners;

- Explore how the child's experiences within their families and networks, including their friends and peer groups, interplay with the risk of harm outside of the home and identify what needs to change;

- Support parents, carers, and family networks to understand what is happening to the child, working with them to ensure they can best meet the child’s needs and play an active part in the solutions and processes to help create safety for the child;

- Understand the risk of extra-familial harm for siblings, for example, where older children are exploited, younger siblings may also be at risk of being targeted.

Within this context, children who may be alleged perpetrators should also be assessed to understand the impact of contextual issues on their safety and welfare.

Assessments of children in such cases should consider the individual needs and vulnerabilities of each child. They should look at the parental capacity to support the child, including helping the parents and carers to understand any risks and support them to keep children safe and assess potential risks to the child.

These interventions should focus on addressing both child and family and these wider environmental factors, which are likely to be a threat to the safety and welfare of a number of different children who may or may not be known to local authority Children's Social Care. Effective information sharing and intelligence gathering is crucial in developing effective coordinated multi-agency responses.

The National Referral Mechanism

The National Referral Mechanism (NRM) is the UK’s system for identifying victims of modern slavery and human trafficking. If a first responder has concerns that a child may be a potential victim of modern slavery or human trafficking (including through county lines) then a referral should be made to the NRM, as soon as possible. A child’s consent is not needed for a referral to be made.

Independent Child Trafficking Guardians (ICTG) are an independent source of advice for children who have been trafficked and somebody who can speak up on their behalf. Where the ICTG service has been implemented, if the first responder considers a child to be a potential victim of modern slavery or human trafficking, they should refer them to the ICTG service. This is in addition to following usual safeguarding routes and NRM referrals. The NRM referral and ICTG referral should be made in parallel.

Last Updated: December 9, 2025

v111